EBITDA Multiple Valuation for Determining Enterprise Value

EBITDA multiple valuation is one of the most commonly used methods in determining enterprise value. As you may remember from our newsletter, “What your business is worth”, there are three main valuation metrics used to value private company equity:

- Industry comparable multiples,

- Book Value, and

- Discounted Cash-flow (DCF)

The industry comparable multiple method is a widely accepted metric in the financial industry for the negotiation and pricing of private companies. It derives the equity value from the enterprise value based on a multiple of a pre-tax earnings measurement less interest-bearing debt plus cash. Exceptionally, some specific industries find revenue multiples or gross profit multiples to be better value indicators.

This newsletter discusses the most common of these earning measures, the EBITDA Multiple valuation.

The EV/EBITDA Multiple

EBITDA stands for Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation, and Amortization. (A seventh letter, “C” was recently added to consider EBITDA before Covid-19 related impacts.)

The banking and investment communities consider the EBITDA multiple metric as a trusted estimation of a company’s enterprise value before any consideration to the capital structure which can vary widely from one company to another. Eliminating interest expenses, taxes and other non-cash items solves this and (theoretically) allows comparison of true operating earnings amongst companies with similar industry and market characteristics. EBITDA can be further adjusted to illustrate a greater quality of earnings by eliminating one-off revenues and expenses which would not be “inherited” by the buyer. For more details on these qualities of earnings adjustments, please refer to our newsletter on “Revealing the true value of your business”.

The reader is undoubtedly aware that EBITDA is not according to GAAP and the measure is broadly criticized as companies can manipulate EBITDA to their advantage. Although the warnings hold true for the general public, lenders and sophisticated investors will audit a company’s EBITDA during their due diligence process and will generally confirm or recalculate the value until they reach a degree of comfort and agreement with the target company.

Factors Affecting EBITDA Multiples

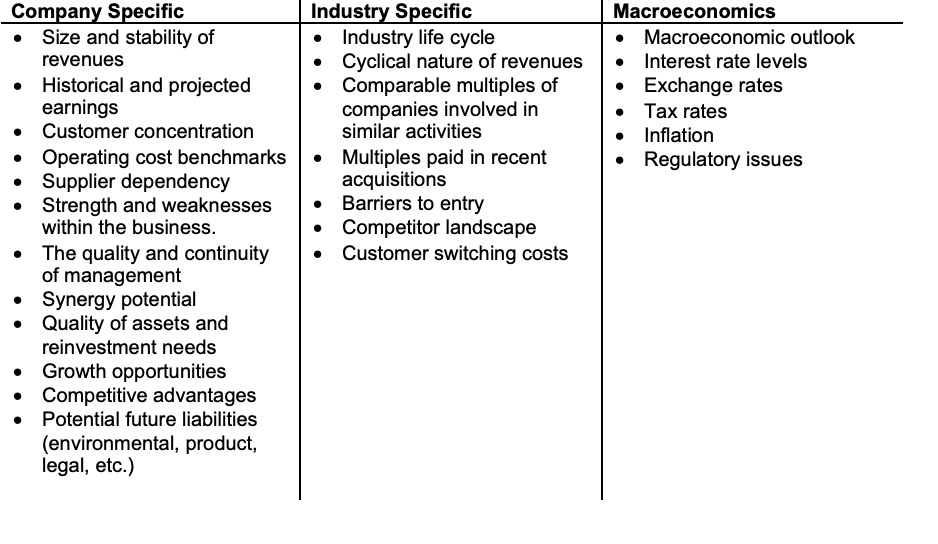

Valuation multiples are largely a function of perceived risk and capital expenditures required to maintain cashflow (the lower the risk and capex the higher the multiple). In our experience, the selection of an appropriate EBITDA multiple must consider several considerations. We have isolated three main categories:

A buyer will typically start its valuation at a multiple based on recent comparable transactions which are, in aggregate, a function of the above-listed industry specific factors, and then add or deduct points based on company-specific factors. From our experience in buying and selling SMEs, the top contributing factors are often:

- Size: For smaller companies, size plays the most important role in attracting a larger number of prospective buyers; it creates a competitive sales process driving higher valuations. Given that most financial buyers have a minimum EBITDA threshold of $5mm or higher, smaller targets cannot actively count on this large pool of buyers to make a competitive bid. This leaves the smaller targets with a smaller pond of prospective acquirers which typically include strategics, smaller private equity funds, management and individuals. While this does not automatically mean a smaller than $5mm EBITDA business will not fetch a higher valuation, its limited pool of prospective investors limits its abiltiy to negotiate price.

- Customer concentration: A high concentration of a company’s sales relying on a few customers is a risk, and risk is inversely related to the multiple. Some buyers may use this argument to drive down a valuation. This is especially true for buyers relying on bank financing as a high customer concentration may impede their capacity to raise sufficient capital to pay a generous price.

But there can be exceptions: Consolidators may not mind, because as they acquire customer-concentrated companies, the concentration “disappears” once the companies are bundled together.

- Growth opportunities and synergies: These are for the seller (or their investment banker) to prove. Buyers will typically look upon a seller’s favourably optimistic forecasts with a strong degree of doubt, especially if they differ from a company’s historical results. No matter how convinced the seller may be of a positive future, few if any buyers will be ready to consider future results in a value calculation without a convincing argument.

The seller will need a to present a detailed, backed-up roadmap with tangible actionable growth opportunities for the buyer to consider future results in its valuation. One cannot stress this enough: buyers are accustomed to seeing “hockey stick projections” that rarely materialize. They will need to be convinced that the target is on the path to significant growth and will capture significant synergies in the near future. Even then, the buyer will not pay the face value to the seller but will want to mitigate its risk by keeping some of the upside for themselves. Academic studies used to show that only 30% of the synergies were paid to the seller, but the trend is now gearing towards 50%.

Negotiating: Know your Floor and Ceiling

The Floor

As a rule, buyers look to try to strike a bargain. But at which point would the price offered be so low that the seller is better off keeping the business? In some cases, this threshold is set at the dividend recapitalization capacity of the target. A dividend recapitalization strategy is when a company takes on additional debt and uses the proceeds to pay a dividend to its shareholders. While not as tax efficient as a sale of shares (capital gain vs. dividend taxation), the shareholders get to keep 100% of the business while creating some liquidity for themselves. Theoretically, an offer from a buyer pegged at such price also implies that the buyer may not be putting much of its own equity into the deal. This is often a showstopper for entrepreneurs who built their business over the years only to see someone buy it without putting much “skin in the game”. For a time-pressed exiting shareholder, an interesting alternative may be to sell to management and receive the bank financing proceeds at closing plus a balance of sale which will be considered as equity for the bankers financing the deal.

In some cases, the floor may also be the book value of the business. This scenario can occur when a business is not capable of generating enough profit to justify the weight of its balance sheet. The same way EBITDA is commonly considered as a proxy of cash flow, book value is considered as the value one would monetize upon liquidating a business. On paper, it would make more sense for a liquidity-seeking shareholder to realize the working capital, sell the capital assets and repay the debt if the total proceeds are greater than what a buyer’s EBITDA multiple based offer. Again, this reasoning has many flaws: first, the audited book value may misrepresent the value of some assets (real estate, machinery) and their inherent tax liabilities which need to be adjusted. Further, there are losses and inefficiencies to be incurred while liquidating a business which are not captured in the book value. Also, proceeds from winding down a company are treated as taxable dividends which are taxed at a higher rate than selling shares (capital gain). Nevertheless, for some sellers, the book value often acts as the mental floor at which the negotiation starts.

The Ceiling

At the other extreme, how much is too much to pay for a buyer to walk away? Enter the concept of “accretive transactions”: one way to quickly understand if a transaction creates or destroys shareholder value is to analyze whether the acquired business is bought at an implied multiple higher or lower than the post-merger combined entity valuation multiple. In layman’s terms, if an acquirer worth 10x EV/EBITDA buys a business at 8x EV/EBITDA, the target’s earnings are “tucked-in” the combined business which is valued at 2 turns of EBITDA higher. This increase goes directly to the equity value. On the contrary, buying a business at a higher multiple than its own intrinsic valuation shaves the difference to the combined equity. As such, any buyer rarely agrees to pay more than its own multiple in buying a business. In fact, a sophisticated buyer will rarely agree to acquire a business at or above its own trading multiple; all transactions must create shareholder value.

What about Sales Multiple?

Valuing a business based on a multiple of its sales may be destabilizing for some as it does not clearly indicate its earnings generation capacity at first sight. Such comparable metrics, for example 2-4x sales for a tech company or even 1x sales for an accounting firm, are considering the significant synergies and similar cost structures between buyers and sellers which, in turn, would result in a fair EBITDA multiple post-merger. As a rule of thumb, and excluding significant growth prospects, all comparable metrics other than EBITDA tend to result in a fair and standard EBITDA multiple once the synergies are accounted for.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, the EV/EBITDA multiple is measure of risk and reward. It will vary from business to business dependent on the underlying risks associated with the selected cash flow of the business and negotiating skills. Cafa can provide the resources to help you in striking a fair deal regardless of your company, or your industry.

Please read the following other related newsletters which may be of interest to you:

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletters to stay on top of industry news, develop your knowledge and receive relevant, real-time advice.